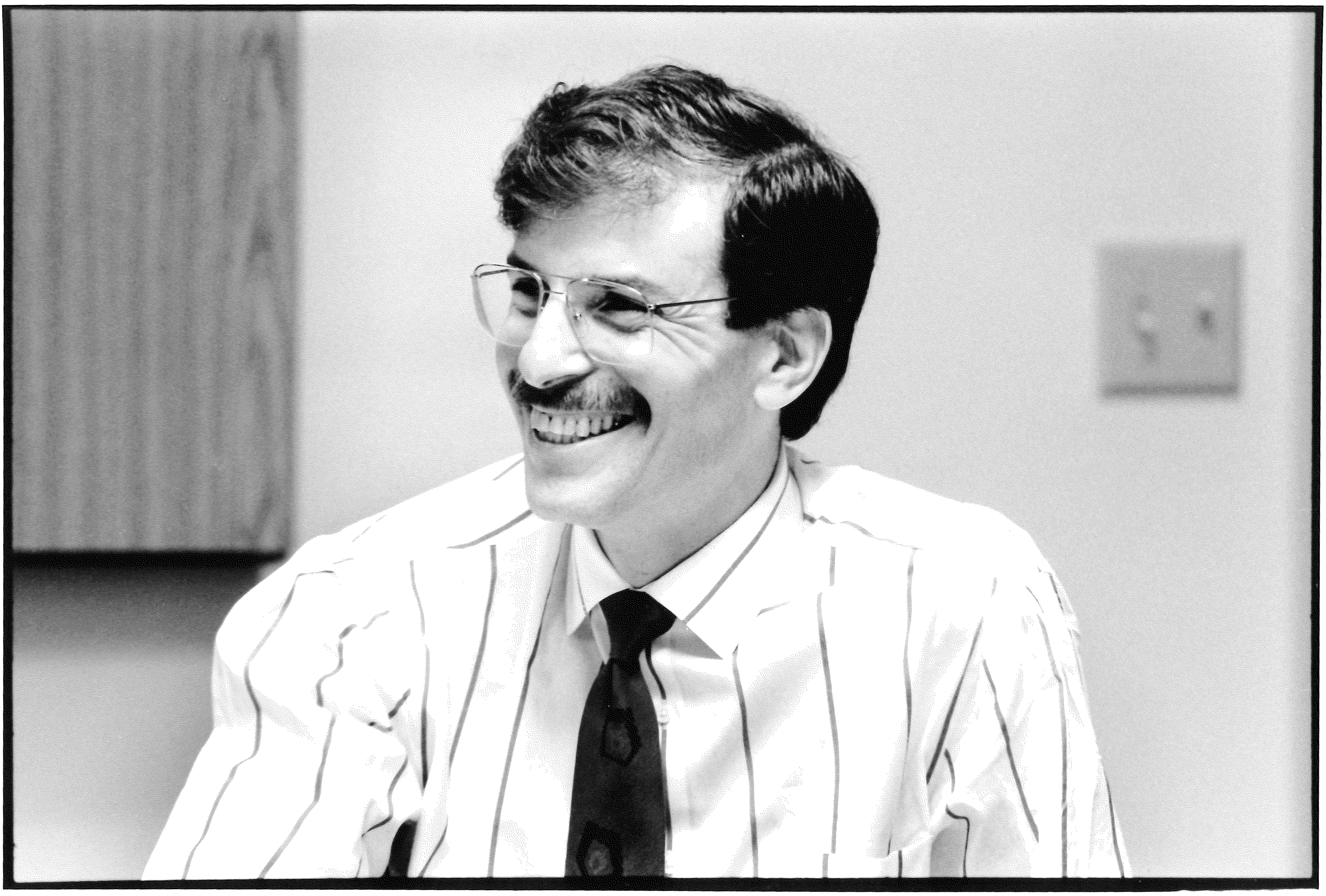

Today in a special guest blog, CEDAC’s founding executive director, Carl Sussman, shares how and why CEDAC was established. Before CEDAC, Carl was a Cambridge Institute fellow in the early 1970s, and in the mid and late 1970s, he was active in crafting the state’s community development finance policies. Carl was the executive director of CEDAC for 15 years and played a pivotal role in launching the Children’s Investment Fund before founding Sussman Associates in 1995.

CEDAC is a product of its time: it grew out of both the post-civil rights era movement for community control in African-American neighborhoods and a period of extraordinary economic development policy innovation in the Commonwealth. Almost lost in the fog of time is the specific local political context that made it possible for policy makers and others to imagine an institution like CEDAC and more remarkably, to win its legislative enactment. Understanding that context helps us to understand why CEDAC came into existence and how it has evolved.

In the late 1960s, a coalition fought the construction of the Southwest Expressway, the extension of Interstate 95 from Route 128 into Boston, where it would merge with another eight lane behemoth, which was called the Inner Belt. It, in turn, would have carved its way through the Fenway, Cambridge and Somerville. Responding to mounting protests, Governor Sargent placed a moratorium on the highway planning and construction in 1970. By then, large tracts of now vacant land had been taken in Roxbury and Jamaica Plain.

Mornings with Mel King

A few years later Mel King, a community organizer and political activist from Boston’s South End who founded and ran MIT’s Community Fellows program, ran for state representative and won. Mel wanted the neighborhoods to gain control of development along the now abandoned Southwest Expressway corridor. To make that possible, he reasoned, community-based development organizations would need access to capital. Making that possible became one of his first legislative priorities.

To help him develop that legislation, Mel invited a collection of community activists, students, professors and others for breakfast at MIT. It became a weekly ritual. Mel cooked fish and grits for whoever showed up Wednesday mornings. These roll-up-your-sleeves working sessions became the Wednesday Morning Breakfast Group (WMBG).

At the time, I worked in Central Square at the Center for Community Economic Development (CCED). The federal Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) funded CCED to serve as a technical support organization for newly-organized community development corporations (CDCs) funded through OEO’s Special Impact Program. These second wave CDCs sought to replicate pioneering prototypes like Brooklyn’s Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation and Cleveland’s Hough Development Corporation.

Soon, I was awakening early Wednesday mornings and climbing the stairs to the windowless room where the WMBG met at MIT. In exchange for breakfast and stimulating discussion, Mel conscripted attendees to serve as foot soldiers to carry out research and writing assignments for the succeeding week’s breakfast meeting.

Not Just a Bill

After debating whether the state program Mel envisioned should restrict its funding to the Southwest Corridor or be made available statewide, the group drafted a bill to create the Community Development Finance Corporation (CDFC) as a statewide development bank. Among other things, the bill created a statutory definition of a CDC in Massachusetts as a not-for-profit organization operating in a geographically defined target neighborhood with a low median income. They had to be membership organizations open to all target-area residents. And, to maintain the principle of community control, a majority of the board had to be elected by these members.

Ten days before the 1974 gubernatorial election, Mike Dukakis, the Democratic nominee, accepted an invitation to attend the Breakfast Group. He voiced his support for the proposed bill, but not the technical assistance provisions because, unlike CDFC’s bond-financed venture fund, technical assistance activities would require an on-going state appropriation.

Even after its enactment in 1975, constitutional issues delayed CDFC’s implementation. That gave the Breakfast Group time to draft legislation that created CEDAC as an independent organization to deliver technical assistance. Chapter 40H, CEDAC’s enabling legislation, was enacted in 1978.

CEDAC & The Evolution of Community Development

After Governor Dukakis appointed CEDAC’s initial board of directors and advertised for an executive director, Mel encouraged me to apply. I did and became CEDAC’s first executive director. It was a modest start. CEDAC’s board chairman and the head of the State Employment and Training Council, Ralph Jordan, let me work out of a cubicle in the Hurley Building while I rented office space, secured phone service, opened bank accounts and attended to the other mind-numbing start-up chores.

Those early months, however, included some of the most consequential decisions for CEDAC’s future: hiring decisions including the early decision to recruit Mike Gondek. Of all the things I did while CEDAC’s executive director, the caliber, commitment, intelligence and skill of those who I hired during my tenure with the agency remains my most important contribution.

Those early months, however, included some of the most consequential decisions for CEDAC’s future: hiring decisions including the early decision to recruit Mike Gondek. Of all the things I did while CEDAC’s executive director, the caliber, commitment, intelligence and skill of those who I hired during my tenure with the agency remains my most important contribution.

Reflecting back on that period, I marvel at Mel’s extraordinary legislative skills. It has never been easy to enact legislation and there was little about either of the WBMG’s bills to draw broad-based support from legislators. But Mel was indefatigable in his demand that legislative leaders do the right thing. In the process, Mel gave birth to the first and most ambitious state effort to spur community-based development in the nation. And it spurred the emergence of a third wave of CDCs. These have proven to be the most durable and productive generation of CDCs – in total, the Commonwealth’s CDCs are responsible for the development of over 18,000 units of housing. Over the last ten years alone, CDCs have been responsible for $4.4 billion in investments, much of it in the state’s most economically distressed communities.

It is quite extraordinary to realize that all of this arose from a community struggle to prevent the encroachment of Interstate Highways into Greater Boston’s inner city neighborhoods. It came also from Mel King’s vision of and commitment to empowering communities. It is a testament as well to Mel’s organizing abilities that Massachusetts created the institutional infrastructure to support the growth and success of the emerging community development industry; one that became a national model. Today, the Commonwealth’s community-based development sector is the nation’s most robust and enduring. In the final analysis, it is this achievement we celebrate by marking CEDAC’s 40th anniversary.